This week, our class met at the Cartoon Museum on Russell Street. The Cartoon Museum is a small space dedicated to showcasing British cartoons and artists. It is one of the few, if not the only museum in London that is dedicated to preserving British cartoons.

The ground floor exhibit was entirely dedicated to showing work titled ‘The Estate of Martin Honeysett’; he was a British Cartoonist, and his work appeared in Punch, and in several newspapers in Britain. He was one of “the greatest gag cartoonists Britain has produced” (Pyne, 2015). There was quite a large range of work of his spread out along the ground floor, commemorating his reign over comics in Britain till his death in January 2015.

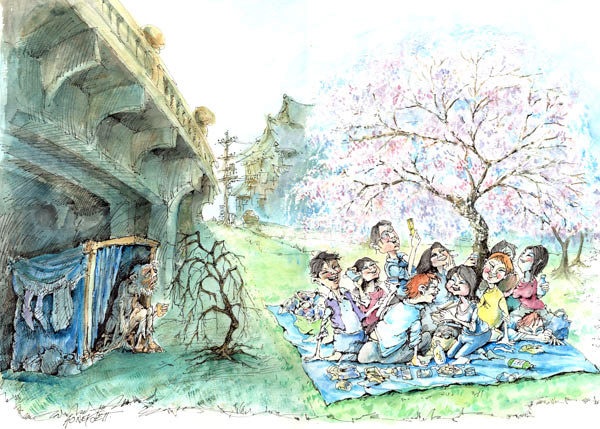

One of the pieces I enjoyed was from when Honeysett was invited to Japan, and subsequently made a series of drawings during his stay there. One particular drawing that caught my eye was titled ‘Cherry Blossom’:

Cherry Blossom (Honeysett, undated):

Cherry Blossom (Honeysett, undated):

‘The arrival of the cherry blossom is celebrated throughout Japan.

The piece stood out to me because of the stark and real contrast that is shown between two classes of citizen, and the ‘celebration’-so to speak- is an extension of your class. To me, this piece made it too easy for me to relate to what I have experienced in Pakistan. You see a wild difference of class in broad daylight, for example you will see upper-class families dining in an outdoor restaurant, and they will almost definitely be ‘harassed’ by a street beggar at their dining table.The nonchalance of those who lead relatively comfortable lives in comparison to the kind of pained expression on those who do not is striking.

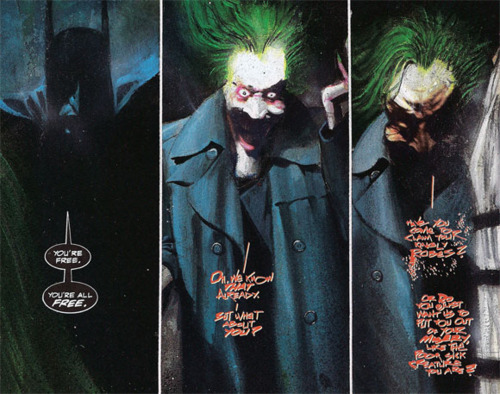

On the upstairs floor of the Cartoon Museum, we were given a short but informative talk by curator of the gallery and a dear friend of our tutor Penn, Steve Marchant. He showed us a page from what is probably the most well-celebrated comics to ever be released, Watchmen (1986). This superhero story has a complex storyline written by Alan Moore, and arguably some of the best drawings by Dave Gibbons. It takes place in 1985, during the cold war, and shows a beautiful, emotional and dense take on nature through the story of a group of washed-up superheroes. Book critic Lev Grossman says about Watchmen, “Gibbons and Moore deployed about a dozen fugually interwoven plots and an intricate system of echoing visual motifs.” (Grossman, 2009).

We were shown a particular page from the comic book which showed Dave Gibbon’s drawing process, and were explained how a single page has to go through many different processes like storyboarding, sketching, ink lining, and several attempts of colouring before the artist can be satisfied with the final results.

An original sketch of Rorschach, a character from Watchmen

An original sketch of Rorschach, a character from Watchmen

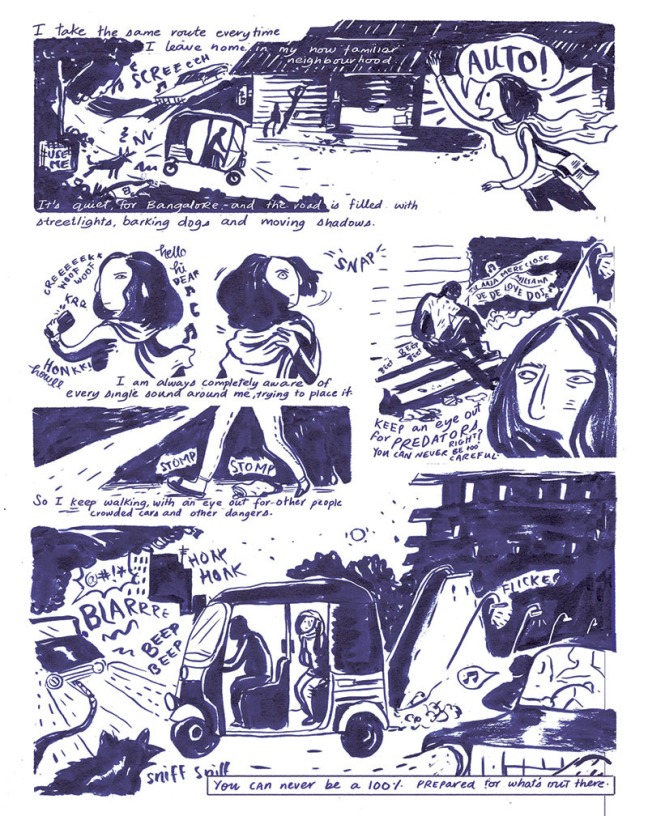

Kaveri Gopalakrishnan: ‘Before You Step Out’ (2015)

Kaveri Gopalakrishnan: ‘Before You Step Out’ (2015)

Scott McCloud talking about gutters in his book Understanding Comics (1993)

Scott McCloud talking about gutters in his book Understanding Comics (1993)

The first two panels of Persepolis

The first two panels of Persepolis

On the left: Me how I see myself in 20 years

On the left: Me how I see myself in 20 years Assassin (Hsiao-Hsien Hou, et al, 2015

Assassin (Hsiao-Hsien Hou, et al, 2015

“Skoghall Konsthall” (Nicholas Jaar, 2000)

“Skoghall Konsthall” (Nicholas Jaar, 2000)